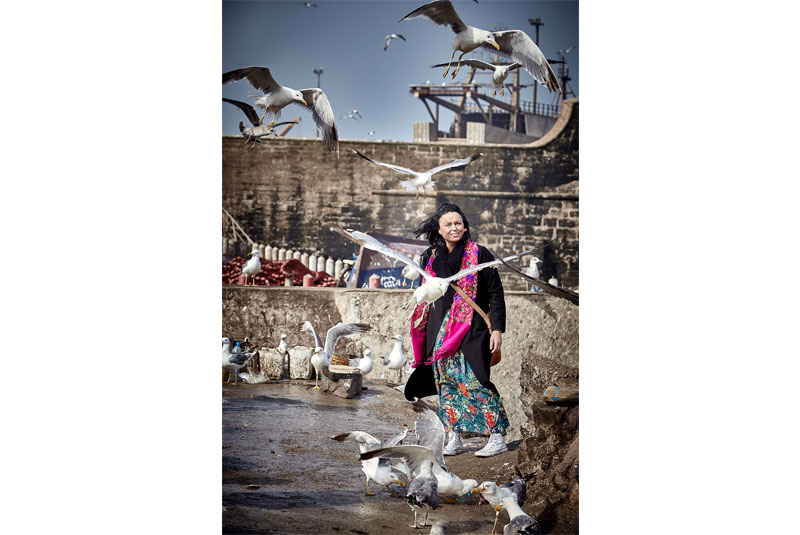

Najat Kaanache, chef-owner of restaurant Nur in Fez, northeast Morocco, often says that she comes from hunger. But the hunger she experienced growing up goes beyond the physical sensation to encompass a gnawing curiosity for food and the world, and a deep desire to change it. After working with the world’s best chefs and opening restaurants in Morocco and Mexico, Kaanache looks back to tell us her story so far

“My father walked barefoot from Morocco to Spain, eating the skin of oranges that people threw on the ground in Andalusia,” says Najat Kaanache. For the Moroccan chef, this is more than an anecdote from her past – it’s the seed that germinated the tenacity to fight for her dreams. “Papa” Kaanache ended his walk in Orio, a small village near San Sebastian in the Basque Country of Spain, famous for its besugo, grilled seabream cooked with garlic, white wine and olive oil. Najat and her two siblings were born here, as Basque-Moroccans.

“I say I come from hunger not because I was hungry, but because I was always in desire of eating things we couldn't afford,” says the chef, who is now based in Fez, Morocco, where she owns two restaurants. “We had the best black olives on the table, the best cumin and the best zaalouk [blackened aubergine], the best lentils and hummus. We had food that made sense for the human body. But the other kids had the most beautiful things – vanilla ice cream and Nutella sandwiches, while we had olive oil and tomatoes.”

Chef Najat Kaanache in a portrait

In her youth, her Moroccan heritage made Kaanache stand out. She felt – and was made to feel – different to the other kids. After studying theatre and film and working as an actress for a year, she moved to the Netherlands in search of a different life. She started out cooking pintxos for art galleries in The Hague, then moved to Rotterdam, where she opened a catering business that delivered food by bike. In 2005, Heston Blumenthal’s alumnus François Geursd opened a restaurant in the city, and Kaanache – who had been fascinated by Blumenthal’s innovations, such as making diners listen to the explosions inside their mouths on headphones – immediately applied.

It was the start of an eye-opening journey. In 2008, she wrote letters to all the restaurants she considered the best on the planet and began to undertake stages to learn about the culinary craft, overcoming any obstacles on the way. “I remember being in Napa and having a shift at The French Laundry at 12 the next day, and not having a place to stay,” she recalls. “I went from shop to shop until a woman who made wine said I could have a room in her home. In New York, I knocked on doors until a couple who owned a store offered me a room. I had to work at Per Se, one of the most luxurious and expensive restaurants in the world and I had one dollar in my pocket.”

Now, Kaanache counts Alinea’s Grant Achatz, Noma’s René Redzepi and El Bulli’s Ferran Adrià among her mentors – she managed to get into El Bulli’s kitchen before the restaurant closed for good in 2011, after trying for years. “I spent more than two years in that space, where you live and they teach you that you have to be yourself, and that’s the hardest and most important thing to learn,” she reflects. “I realised that I’m not here to take what the world is giving me, but to bring something into the world.

North African mole with chicken by Kaanache

“I still have that little child inside of me, but now I hold her and I tell her: ‘It’s okay you didn’t have vanilla ice cream or Nutella, now you have everything you want and even so, you don’t have the desire for it any more’. Because now my hunger is bigger than that. I want to give an opportunity to all those other people who couldn’t have those things, I want them to be able to dream.”

Morocco calling

In 2016, Kaanache was living in Mexico, learning about cocoa and the process of making chocolate, when she received an unexpected call. Stephen di Renza, Yves Saint Laurent’s former creative director, had a space in Fez he wanted her to see. Kaanache immediately knew it was perfect. But moving permanently to Morocco also brought on a process of reckoning with her own culture and heritage.

“Being Moroccan means to belong to a culture that doesn’t have much power, no big designers, no famous cars – there isn’t something that just distinguishes Morocco, aside maybe from tagine [a slow-cooked stew made in an earthenware conical pot of the same name] and cous cous,” reflects Kaanache. “But when I moved there, I met with my grandfather, and he told me he didn’t know what a tagine was and he’d never see one.”

Restaurant Nur

For the chef, it was a wake-up call. Her mission at her restaurant Nur – which means ‘light’ in Arabic – became to represent the past, present and future of Moroccan cuisine on the plate. Learning from her grandfather and the indigenous people of Morocco, Kaanache immersed herself in a study of their culture. “For me, the flavours of Morocco are the colours, the ancestors, the magic, the mysticality and the power of people,” she says. “The traditional dishes are so well divided, with a 1-1-1 ratio of greens, carbohydrates and protein.”

Her journey also led her to better understand preserving, a practice with a deep history in a hot country like Morocco. Most of the food at Nur is now preserved in glass. Vegetables and proteins are cured, blackened, pickled and preserved in many ways. This research also gave her a better understanding of food history. “In Spain, people eat Andalusian escabeche [preserved fish], but escabeche is an Arab word,” she points out.

Nur is hidden in the Medina of Fez, an ancient, labyrinthine area home to many historical buildings and a UNESCO World Heritage site. Kaanache jokes that to find it, you need an intergalactic guide like in Star Wars. Here, the chef serves her own, highly personal interpretation of Moroccan cuisine in fine dining form – a three-hour journey through the country’s food culture that may take in beet-cured bonito with mango and spinach or a north African mole with chicken inspired by her time in Mexico.

Arabic octopus with beets by Kaanache

When the restaurant opened in 2016, for two weeks it was almost empty. But Kaanache reached out to chef Grant Achatz and restaurateur Nick Kokonas of Alinea in Chicago, who offered to list Nur on their reservation platform Tock. This allowed the restaurant to be found by tourists coming from the US and Europe. “In less than two weeks, the restaurant was full,” says Kaanache. “For almost three years, it was full every day. It’s an exception in Fez, because it’s the only restaurant where people book tables months in advance.”

But of course, no one could have predicted the events that would unfold in 2020. “Now, with no air traffic, we are really struggling,” says Kaanache. “The restaurant has been closed for four months and I don’t expect we’ll reopen until November. Morocco is a tourism destination and the hospitality industry has been hit very hard by the closures. I’m still paying all the bills, as well as social security for my employees. I live on top of the restaurant and every day I go down and offer a glass of milk to the local kids who don’t have one. But I’m a dreamer and I like to keep it that way.”

Post-pandemic dreams

As well as Nur, Kaanache owns two more restaurants – Nacho Mama, a Mexican cantina in the Medina of Fez, and Cús, a Moroccan street food joint in Mexico City. But her dreams go well beyond expanding her restaurants. “I wish the world could look more at Africa, because it’s such a rich continent,” she says. “We’re not poor. We're not begging for 50 kilos of flour. We're asking – and this is a collective sentiment, I speak for African people in many countries – to be seen as people.”

The chef would also like to see more visibility for the women in the continent. “In Africa, women rule the kitchens,” she says. “Hospitality here is run by women and women’s hands, in hotels, restaurants, riads, in the homes – anything that has to do with hospitality has women behind it, but there’s not enough recognition. We are asking: ‘Can you look at us? Can you go around our continent and see the extraordinary people who are also suffering with this pandemic?’”

As for her own individual dreams, Kaanache has one that she keeps very close to her heart. Just uttering the words brings tears to her eyes. “When I was a child sleeping in a house with no roof, I used to look at the stars and think that I could be one,” she recalls. “When I couldn’t taste ice cream or Nutella, I imagined their flavours – I’ve always lived on an imaginary planet in my brain.

“My dream would be to cook with Elon Musk on the Moon, to create the first dish there. I went from having nothing to writing maybe 25 letters to Elon Musk asking for this. I want people to think that everything is possible, that if you really believe and have the desire, the only person who can stop you is yourself. So I keep on dreaming.”

Watch the video interview with Kaanache:

Header images: Kaanache and her dish of beet-cured bonito with mango and spinach

‘50/50 is the new 50’ is a content series created by 50 Best and supported by S.Pellegrino with the shared aim of promoting equality, inclusivity and balance in the hospitality sector and beyond.

Visit the Restaurant Recovery Hub and the Bar Recovery Hub to explore useful resources and read the stories of chefs and bartenders around the world. Follow 50 Best on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube for the latest news and videos.